Perinatal and Mood Disorder Treatments

“It is the vision of PSI that every woman and family worldwide will have access to information, social support, and informed professional care to deal with mental health issues related to childbearing. PSI promotes this vision through advocacy and collaboration, and by educating and training the professional community and the public.”

What is Perinatal Mood Disorder Treatment?

Postpartum Support International (PSI) brings together families, communities, and professionals working to support families during pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and the postpartum period. Childbearing can bring an onset of various symptoms before, during, and after pregnancy.

The perinatal period is the time from from conception through the first year after giving birth and considers risks at any stage to include fluctuations in hormones in pregnancy, post-birth, onset and weaning of lactation, re-emergence of menstruation, onset and/or relapses in mental health disorders, and more.

Perinatal or postpartum mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD) is the term used to describe distressing feelings that occur during pregnancy (perinatal) and throughout the first year after pregnancy (postpartum or postnatal). Feelings can be mild, moderate, or severe.

We are here to help. It indeed takes a village! You are not alone.

Parent and Caregiver Roles Defined

PMADs can impact anyone and everyone involved in the childbearing process. The following are the definitions are some parent and caregiver titles:

- Intended Caregiver(s): Who the baby is going home with (i.e., biological, adoptive, fostering, etc.)

- Relinquishing Caregiver(s): Person(s) placing the baby in another home (i.e., Surrogacy, giving their baby to Intended Caregivers via adoption, etc.)

- Adoptees: Adopted child(ren)

PMAD Can Affect Anyone

PMADs do NOT discriminate, can impact anyone, and socioeconomical status is NOT protective. The risks of untreated PMADs can impact things such as:

- Relationship issues

- Poor adherence to medical care

- Exacerbation of medical and mental health conditions

- IPV/separation/divorce

- Loss of interpersonal and financial resources

- Disability/unemployment, child neglect and abuse, developmental delays and behavioral problems

- Increase in substance use, infanticide, homicide, and suicide

- Entering parenthood creates unavoidable adjustments, challenges, assumptions, and expectations

PMAD Risk Factors

Exacerbating Psychosocial risk factors of PMADs can include:

- Inadequate or nonexistent partner/social support

Interpersonal violence - Other relationship stressors and complex developmental trauma

- Financial stressors such as poverty

- Childcare stressors

- Recent losses or moving

- Barriers to medical and mental healthcare

- Systemic and institutional racism and discrimination

- Climate stressors, natural disasters, pandemics

- Seasonal Depression and/or Mania

- Complications in fertility, pregnancy, birthing, breastfeeding, etc.

- Health challenges for anyone involved, including the baby and its treatment

- Returning to work

- Unresolved grief or loss

- Miscarriage and abortion

Evidence-Based Psychotherapeutic Treatment Models (EBT)

- EMDR

- Attachment and Parent-Child Therapies

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Couples Therapy

- Play Therapy

- Sand Tray Therapy

- Expressive Arts

- Animal-Assisted Therapy

- Group Therapy

- Psychopharmacology

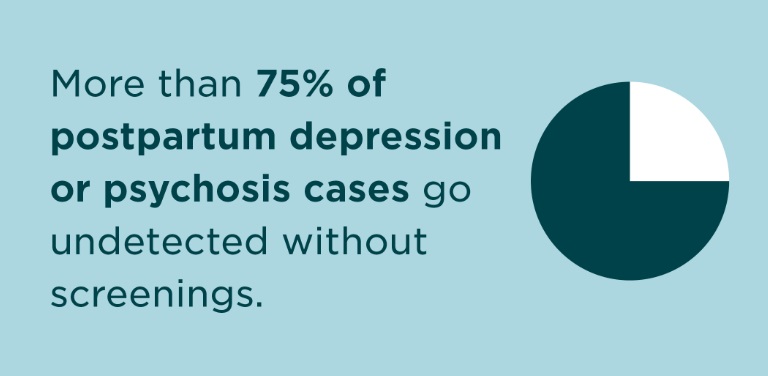

Statistics from Landmark Studies of US Mothers

- 21.9% had depression during the first year of postpartum

- Of those 21.9% of women:

- 26.5% of the episodes began BEFORE pregnancy

- 33.4% of the episodes had their ONSET DURING PREGNANCY

- 40.1% of the episodes began DURING THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD

- Of those 21.9% of women:

- 68.5% had a primary diagnosis of unipolar depression

- 66% with Major Depressive Disorder (MMD) had comorbid anxiety disorders, most commonly Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- 22.6% were diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder

- 19.3% encoursed thoughts of harming themselves

Medications: 26% of those who continued their medication relapsed in pregnancy; 68% of those who DISCONTINUED their medication relapsed in pregnancy. Chances of relapse are strongest during the postpartum period.

YOU ARE NOT ALONE!

Prevalence of PMAD in Fathers

In national studies reported in 2006-2010, 10% of new fathers scored int he range of moderate to severe depression. Maternal depressional increased the risk of paternal depression and was the strongest predictor of paternal depression even beyond the father’s own history of depression. Factors in Partner Depression: Feeling burndened or trapped; Financial responsibility pressure; Feeling outside of the circle of connection; Missing sexual intimacy; Sleep depirvation; Isolation and loneliness; Loss of their partner and closest friend due to pregnancy; Poor social support network and societal stigma

Society views men as stoic, self-sacrificing, and above all, strong. When men feel none of those things as new fathers, they don’t want to admit it or seek help. For this reason, Postpartum Support International is an enthusiastic supporter of IFMHD as a means to take a whole-family, father-inclusive approach by shedding light on the best practices and related resources for dads, their partners, and those who support them. Founded by paternal postpartum depression survivor Mark Williams and fatherhood mental health expert and PSI board member Dr. Daniel Singley, IFMHD involves taking the day after Father’s Day to launch a focused social media campaign which highlights key aspects of fathers’ mental health.

LGBTQIA+ PMAD Experience

Queer people’s experiences of conception, birth, and parenting are under-recorded and under-researched. Research on pregnancy continues to be centered within heterosexual relationships. Lesbian women in the postpartum period reported a higher prevalence of PMADs and increased rates attempting/considering suicide. Bisexual women in the postpartum period reported an increased risk of PMADs if currently partnered with a man compared to with a woman. Queer people’s experiences of conception, birth, and parenting are under-recorded and under-researched. Research on pregnancy continues to be centered within heterosexual relationships. Numbers of LGBTQIA+ people having babies is unknown in most countries due to universal data rarely being collected on the gender or sexual orientation of those who are pregnant or their partners.

Gay male parents reported LESS positive feelings at the end of pregnancy when compared to lesbian mothers and MORE positive feelings about parenthood in the early postpartum weeks when compared to heterosexual parents. No research focusing on gay men’s experiences of or involvement int he actual surrogate pregnancy and birth have been undertaken. Information on the new fathers’ perinatal mental health is scarce and deserves recognition and services.

Trans Gestational Parents need more esearch to determine prevalence rates. Baseline depression and suicide rates among transgener indidvidual are higher than adult average. Anxiety is three ties higher in transgender persons. Increased discriminiation, insufficient healthcare provider training and awreness, lack of societal andor familial support. PMADs may be more prevalent in trans gestational parents.

PMAD and Persons of Color

Explaining the injustices of perinantal mental health in People of Color (POC) is difficult to say the least. There is evergrowing concern for black and brown women, men, and families who are in the midst of enduring and absorbing generaltional traumas and systemic racism.

PSI has always been committed to helping Black families, yet this moment is without a doubt a renewed call to action in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. These statistics are not new but important to share – and they remain unacceptable as ever:

- CDC data confirms that Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications, and twice as likely to lose an infant to premature death.

- According to the NIH, Black mothers are several times more likely to suffer from Postpartum Depression but less likely to receive treatment and follow-up.

- During COVID-19, we are painfully aware that Black persons are at significantly greater risk of contracting the potentially deadly virus and less likely to receive proper treatment, due to the same root causes of the effects of long-standing racism in social and healthcare systems.

- Compared with White mothers, mothers of color say they were not always able to complete the recommended series of prenatal visits, mainly because of lack of transportation or scheduling conflicts.

- Compared with White and Hispanic mothers, Black mothers report feeling their provider did not spend enough time with them and have lower confidence they will receive the care they need or cannot openly speak about their pregnancies.

It is imperative that we do our part to fight racism and improve these unjust outcomes!

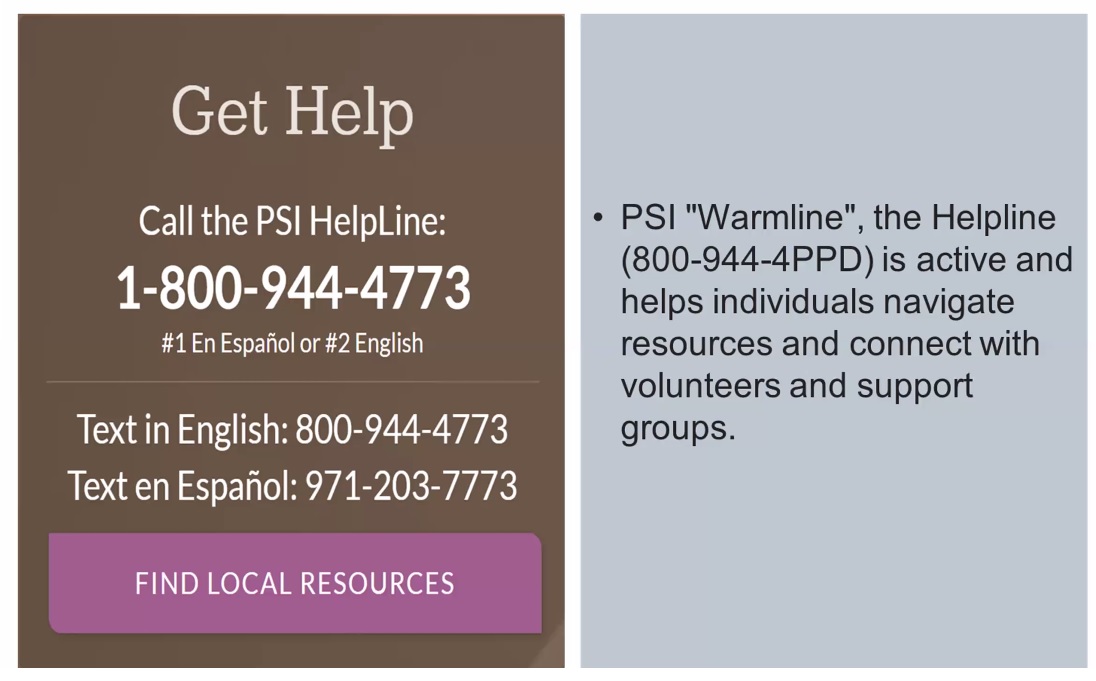

Helpful Resources

- Postpartum Psychosis requires calling 911 immediately! Check your state’s definition of “mental health arrests.” Inform 911 this is a MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS for a mental health professional to coordinate and assist

- Postpartum Support International Website including support groups for all populations

- National Maternal Mental Health (MMH) Hotline: 1-833-9-HELP4MOMs (1-833-943-5746) Open 24/7/365; Call or Text

- www.postpartum.net/get-help/locaitons/

- 14,000+ members and trained staff on PSI Closed Facebook Group

- The Center for Women’s Mental Health, which provides state-of-the-art evaluation and treatment of psychiatric disorders associated with female reproductive function including PMAD

- Paternal Perinatal Mental Health